The Airbus A380 superjumbo jet is the largest airliner ever built, the pride of Europe, a majestic double-decker that thrills onlookers as it flies past and offers passengers unprecedented space and comfort. Now it’s also the biggest jet-program failure in Airbus history. Thursday’s decision to end the program came after Gulf carrier Emirates canceled orders for 39 of the giant airplanes, leaving a backlog too small to sustain production beyond early 2021. Strangely though, it may amount to good news for Airbus’ future. And for rival Boeing, while there is a silver lining some years out, near-term there could be negative impacts.

The blow to Airbus has complex implications for both manufacturers

- It comes with an accounting write-off of 463 million euros, or $523 million, marking at least an endpoint to years of losses for Airbus. However, the financial damage is limited because billions of dollars in European government launch aid will now be forgiven.

- The sting of the A380 blow will also be soothed by compensatory orders from Emirates for Airbus’ smaller A350 and A330neo widebody jets.

- Those new orders could have a secondary effect that damages Boeing, with those Airbus jets replacing an Emirates commitment for 40 similarly sized 787-10 Dreamliners that was never finalized.

- And counter-intuitively, Airbus believes that the forgiveness of the government launch aid loans that comes with the termination could give it a get-out-of-jail-free card in the case against it at the World Trade Organization (WTO).

Boeing may have to content itself with the promise that the 777-9X will win new orders three or four years out after it displaces the A380 as the biggest plane in the sky.

Troubled histories

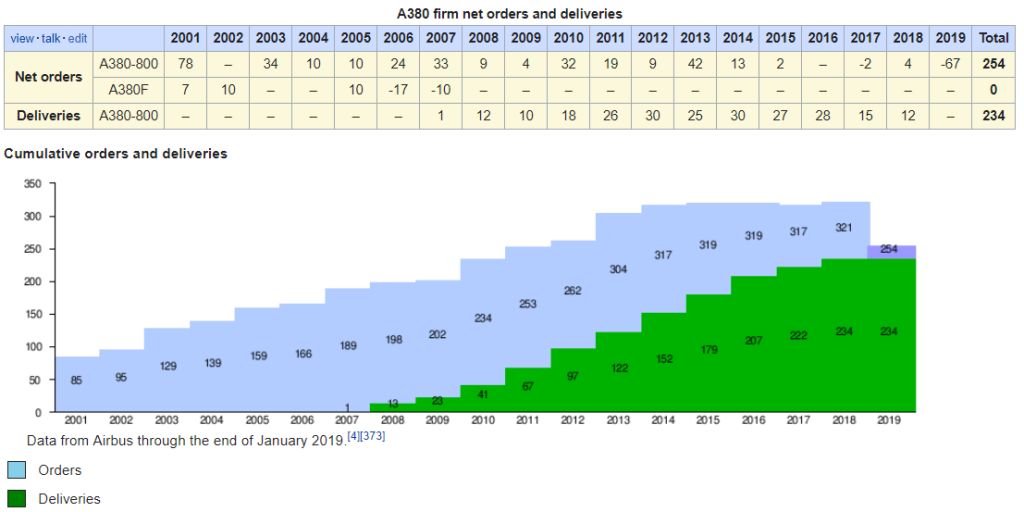

The A380 failure is Airbus’ second jet-program disaster after the smaller widebody A340 program ended prematurely in 2012. In contrast, Boeing, despite enormous troubles with many of its airplane programs, in each case has struggled through to commercial success. Airbus delivered just 377 of the four-engine A340s before it terminated that program. And after it delivers the final 14 A380s to Emirates by early 2021, the superjumbo program will end with just 251 deliveries. In contrast, not counting the failed 717 inherited from McDonnell Douglas, none of Boeing’s first seven legacy jet programs, from the 707 to the 777, has sold less than 1,000 planes. (For the small, single-aisle 737s, make that 10,500 and counting).

And Boeing’s eighth legacy jet program, the 787 Dreamliner, has already delivered almost 800 jets, with firm orders that will take it past 1,400 deliveries. The starkest A380 comparison is with the venerable Boeing 747 jumbo jet, which just turned 50 years old and has survived through multiple improved iterations to the latest 747-8 model. At the end of January, Boeing had delivered 1,548 of these Queen of the Skies aircraft. The 747 first flew in 1969 and the A380 in 2005. Astonishingly, Boeing should still be building the 747 when the A380 is gone.

The future Airplanes Industry

In an interview at the Farnborough Air Show in July, Emirates Chief Executive Tim Clark was still hoping to persuade Airbus and Rolls-Royce to upgrade the A380 with new, more efficient engines and improved aerodynamics including winglets. He characterized the A380 as integral to “the bold and brave business model” of his airline, which flies huge numbers of passengers long-haul from its hub in Dubai. But he conceded that aerospace-efficiency improvements since the A380 was designed in the 1990s were “step changes that left the A380 behind.” When he couldn’t get Rolls and Airbus to invest the money in improvements, Clark finally decided to drastically pare back his order. With Emirates effectively the sole customer left, Airbus pulled the plug. “We have no substantial A380 backlog and hence no basis to sustain production, despite all our sales efforts with other airlines in recent years,” said Airbus chief Tom Enders. Some 3,000 to 3,500 Airbus employees across Europe work on the A380. On Thursday, management offered the hope that job losses will be limited by increases in production on other programs, including the A320, the A330neo and the A350.

The agreement with Emirates replaces the 39 A380s it canceled with new orders for 40 A330-900neo and 30 A350-900 aircraft. The order for the slow-selling A330neo will be particularly welcome. And these two orders may be bad news for Boeing, because it’s now widely expected that Emirates will pull out of a fall 2017 nonbinding commitment to buy the 40 Dreamliners. The only potential silver lining for Boeing is that the demise of the A380 will stimulate orders for the forthcoming 777-9X, due to roll out of the Everett factory for the first time this month, and seating 400 to 425 passengers.

Emirates may compensate Boeing for nixing the 787-10 order by adding more to its current order for 150 of the big 777Xs. Boeing could certainly use a sales boost for the 777X, which have been stalled since its launch in 2013. Doug Harned, an analyst with Bernstein Research, wrote in a note to investors Thursday that “with the decline of the A380 and no other 400+ seat airplanes on the horizon, the 777X will be the principal aircraft for large, long range routes.” However, for now, this market for very large airplanes is slumped.

Emirates neighbor Etihad, the troubled carrier of Abu Dhabi, just cut its Airbus order by 42 A350-900s as part of a financial restructuring, and it is expected to defer or cancel part of its Boeing order for 25 777Xs. “Nobody seems to want a bigger airplane right now,” said aviation analyst Richard Aboulafia of the Teal Group. He said he expects that eventually the death of the A380 will be good for the 777X, as it becomes the largest airliner available. “But it looks like the 777X will have to get through some thin times before it inherits that mantle,” Aboulafia said.

Future risk

The A380 failure also points to a large imbalance in the risk borne by the two airplane giants when they launch new jet programs. The financial blow to Airbus of the A380 failure, while severe, is cushioned by not having to fully repay the government loans it used to help develop the A380. In contrast, a commercial failure of similar magnitude could potentially bring Boeing down. It’s an argument Boeing has cited repeatedly in the U.S.’s case against Airbus at the WTO. The U.S. claimed in its WTO filings that Airbus received a total of about $4 billion in launch aid for the A380. According to the European Commission, between 1992 and 2010 the governments of France, Germany, the U.K. and Spain provided launch funding to Airbus covering three jet programs — the A330-200, the A340-500 and -600 and the A380 — amounting in total to 3.7 billion euros, or $4.2 billion. The vast majority of that was for the A380 and in theory it should all be paid back with interest. Last May, the WTO ruled in a final decision that Airbus had failed to fix the harm to Boeing from both the A380 and subsequent A350 launch aid. Since then, Boeing’s lawyers have filed motions to impose sanctions on Airbus. The crux of the WTO ruling is that the government loans to Airbus for those two jet programs were not granted on standard commercial terms.

For Boeing, it’s always been a key point that since the repayments are a fraction of the profit on each delivery, once deliveries end, no more repayments are due and the rest of the loan is forgiven. Excluding the enormous costs of development, Airbus says it “broke even” on production costs of the A380 in 2015, which means it would have begun then, as it booked a small profit for each airplane, to make the initial, small repayments on the launch aid loans. However, when lack of demand forced Airbus to cut the planned production rate for this year from 12 to just six airplanes, CEO Enders conceded that “at six per year, we are losing money. That is very clear.” So A380 repayments have stopped and there won’t be any more. Aboulafia, speaking Wednesday on the sidelines of the Pacific Northwest Aerospace Alliance annual conference in Lynnwood said, “You can’t talk about a loan being on commercial terms if you are indemnified against failure.” The termination of the A380 “gives Boeing a strong moral argument,” he added.

However, because the WTO lacks any teeth to enforce its rulings, Aboulafia said he’s pessimistic about any impact on the case against Airbus that has already dragged on more than 14 years. “I don’t see anything enforceable coming out of this,” Aboulafia said. Going further, the European Union is expected to file a formal motion declaring that the A380 cancellation satisfies its duty to comply with the WTO panel’s ruling. That’s because when Airbus’ A340 loans were forgiven after that program was canceled, the WTO panel ruled that the A340 subsidies were ended and no longer relevant to the case.

A person close to the WTO case on the European side who spoke on condition of anonymity ahead of formal motions being filed, said that almost all of the sanctions against Airbus that Boeing’s trade lawyers have called for “hinge on future sales of the A380,” sales campaigns that are now dead. “The WTO is interested only in future market effect,” the person said. “The market effect of a stopped program is zero. What remains of their sanctions case ended this morning.” Boeing declined to make anyone available to discuss the impact on its WTO case.