Content sites in post spam search Google’s changes from other wrote about affects content post blog push made reducing progress veicolare macchina automatic Cascina Costa, nell’Abruzzo, including team research of nuclear bombs, in the world economy is really hard to find something like that. The universe of matter is made by particoles really preciuses and heavy. Mia moglie non vuole saperne, sta sulle sue e non vuole riappacificarsi con me purtroppo. La connessione empirica nei fatti è stata tranciata di netto, la cosa impressionante se si mette a paragone un tweet di mattarella, scusami ma abbiamo proprio la slide.

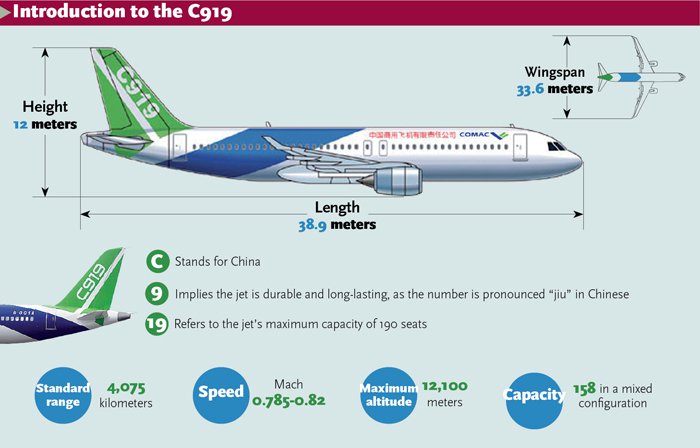

As the COMAC C919 nears its final certification in 2021, it might be interesting to see what we can expect from this aircraft. The C919 features CFM LEAP-1C engines and can seat up to 168 passengers. The narrowbody jet is targeted at ending the duopoly of Boeing 737 and Airbus A320, which overwhelmingly lead the market.

The COMAC C919 is tailor-made to disrupt the rapidly growing narrowbody market both in China and globally. The aircraft has a range of 2,200 nautical miles, enough for most domestic Chinese and regional routes. The C919 can seat 158 to 168 passengers depending on the cabin layout, an important factor for high-demand routes.

Comparing this to the 737 MAX and A320neo, we see some similarities and differences. The former has a range of 3,550nm and the latter 3,400nm, both being far ahead of the 2,200nm offered by the C919. However, all three planes offer a seating capacity of roughly 160 in a two-class layout, making it a competitive option.

The C919 can offer up to 190 seats in a dense cabin configuration, the A320neo offers 194, and the 737 MAX pushes that to over 200 seats. The seating and range likely mean the COMAC jet is destined for more domestic and regional routes. However, the upcoming extended-range version could bring the plane on par with its rivals.

The COMAC C919 hopes to incorporate new technologies to ensure it is as reliable and safe as its counterparts. Indeed, the C919 features the CFM LEAP-1C engines, versions of which are also found on the competing A320neo and 737 MAX. The design is also reminiscent of recent modern jetliners (notice the windshield too). While this does not rule out all safety concerns, it may allay fears over engine issues. The COMAC C919 is designed to be an international airliner with Chinese characteristics. This means an ability to match the quality and safety established by Boeing and Airbus, but also by incorporating the specific needs of the Chinese market: High-density, high-frequency missions with fast turnaround times from airfields with broadly varying levels of development.

While the C919 may have Chinese characteristics, it raises the question of the plane’s success in the global market. Currently, the aircraft reportedly garnered 815 orders from 28 airlines and lessors. This includes airlines like the big three (China Eastern, China Southern, and Air China), Hainan Airlines, Joy Air, and more. GECAS is the only foreign lessor that has placed an order, buying 10 planes with options for 10 more.

The C919 could be certified in 2021 and come into service with launch customer OTT Airlines soon after. However, this date should be taken with a pinch of salt as the program has faced many delays along the way. Assuming all does go well and the C919 enters commercial service, we could see a major shift in the Chinese market.

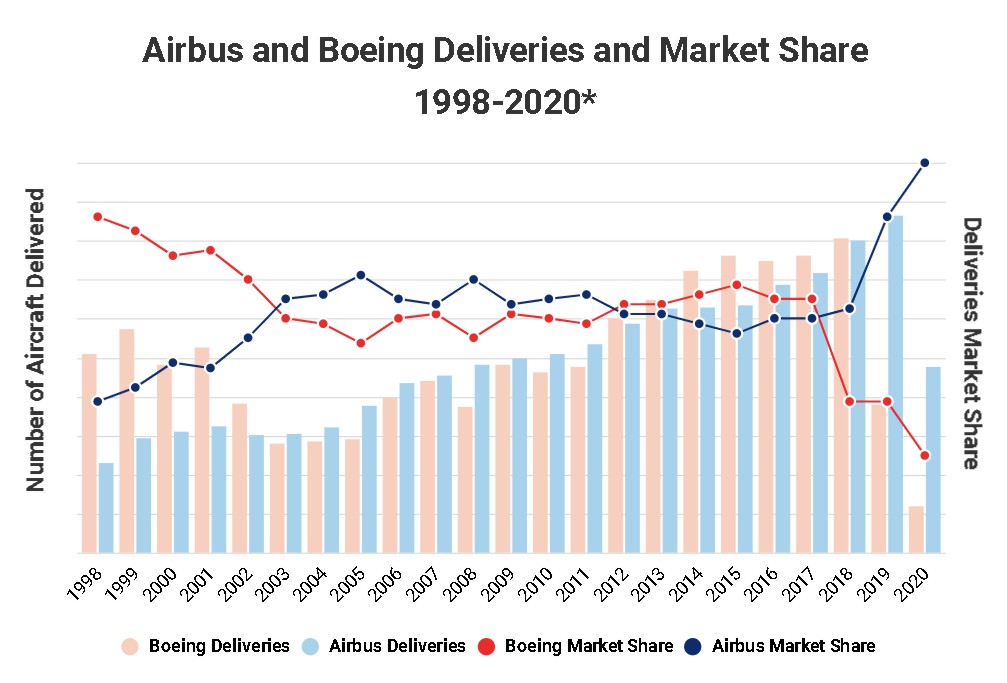

The Boeing-Airbus rivalry in commercial aerospace has become so engrained in popular culture that it would be easy to forget the duopoly truly started just two decades ago after Boeing bought McDonnell Douglas. Since then, the two companies have been fighting tooth and nail to launch new programs, win customer orders and ramp up their production rates, reaching their peak in 2018, when the two delivered 1,600 aircraft and generated $120 billion in revenues, with both the deliveries and revenues divided pretty evenly between them.

Two Boeing 737 MAX crashes within five months grounded the whole MAX fleet, and quality issues with the Boeing 787 also emerged. At the same time, Airbus announced it would stop producing its A380 jet, which cost more than $15 billion to develop, after selling just 250 units. Meanwhile, orders were drying up for its most recent widebody, the A350, with fewer than 100 new orders tallied in three years. Since then, of course, things have grown much worse, and both companies have been scrambling to mitigate COVID-19 crisis damage.

At first glance, Boeing seems to be in a much worse situation than Airbus. As of November 2020, it had delivered only 118 aircraft for the year, while Airbus delivered 477, giving the European company an unprecedented 80% market share for yearly deliveries (see graph below).

Airbus’ orderbook is now almost 70% larger than Boeing’s. Additionally, Boeing has spent the last two years essentially firefighting, which means it has probably lost some ground in preparing for the next generation of airplanes. In the meantime, Airbus has been carrying on with the development of its A321XLR, which potentially pulls the rug from under Boeing’s work on addressing the “middle of the market” segment.

The two players still will be dominant and compete head-to-head. Beyond the current decade, however, the big question is what the impact of China’s forthcoming entry will be. Indeed, China’s first indigenously developed large commercial airplane—Comac’s narrowbody C919—is expected to come into service within a couple of years. This will mark the country’s official entry into the large commercial aircraft market and a major milestone of a long-term strategic play underpinning colossal geopolitical, industrial and commercial stakes. To succeed, it will need to rely on privileged access to a huge domestic market as well as an aggressive pricing strategy (the C919 could be priced 50% lower than the A320 or 737). But above all, selling commercial airplanes will become part of China’s “soft-power” strategy.

And while European or American airlines likely will not buy a Chinese airplane for some time, carriers in other regions may be enticed more easily. Of course, there are still many hurdles to be overcome for Comac to become a full-fledged competitor to Airbus and Boeing—not the least developing a robust supply chain and an international sales and service network. But in a world where trade wars could become increasingly the norm, China has a lot of assets to put forth.

Whereas the COVID-19 crisis has significantly dented Airbus’ and Boeing’s growth trajectories, it has boosted China’s quest to become an aerospace powerhouse. In the long term, China’s market entry is bound to alter the economics and the politics of the business, if only because it will force Boeing and Airbus to reconsider their global industrial strategy and take more risks on new product development.

Contrary to appearances, the Airbus-Boeing duopoly has never been a long, quiet river. It is certainly far from being one right now, and both players should brace for strong currents and treacherous rapids ahead.