In the past, astronauts have captured orbiting satellites—most notably in a series of space shuttle missions to repair and upgrade the Hubble Space Telescope. But these operations have been performed only in low Earth orbit, many thousands of kilometers closer to Earth, and each mission puts human lives on the line. Sending humans out to GEO would put them at even further risk, as they’d be exposed to more intense radiation from solar particles and cosmic rays. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is developing a robotic servicing spacecraft that can work on satellites that were never designed to be ¬serviced—which is pretty much all of them in orbit today. This public-private partnership, the Robotic Servicing of Geosynchronous Satellites (RSGS) program, builds on a decade of work by DARPA (where coauthor Roesler works) and the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory (where Jaffe and Henshaw work), as well as the efforts of university researchers and space agencies around the world. There are over 400 geosynchronous satellites orbiting 22,000 mi (36,000 km) above the Earth.

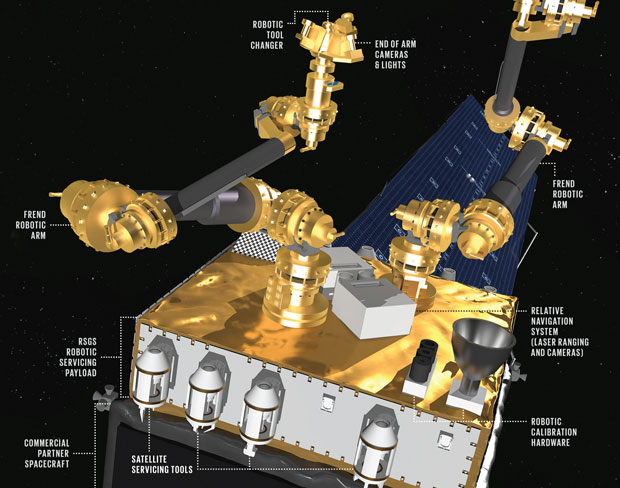

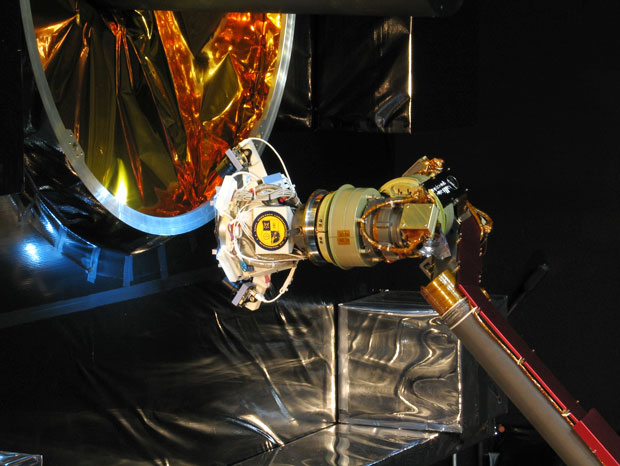

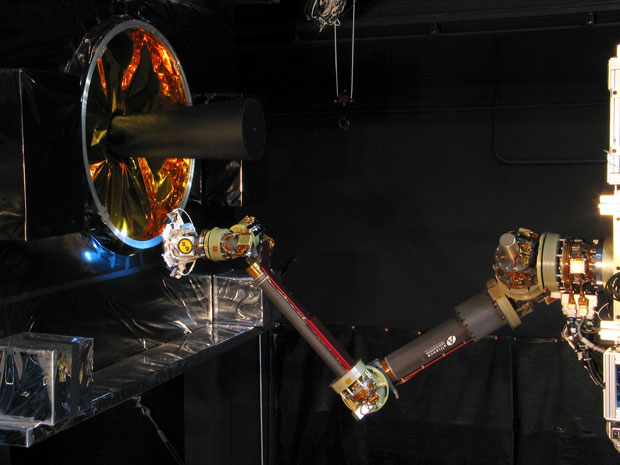

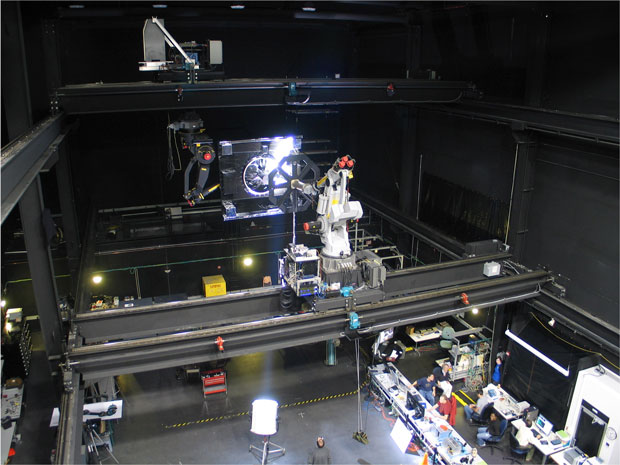

RSGS will have two main components: a “bus” and the payload. The bus will handle basic spacecraft activities like propulsion. The payload will contain all the specialized instruments and hardware needed to perform servicing tasks. This sketch is a preliminary vision of what the payload will look like. It includes two robotic arms, a laser-ranging system,and numerous cameras (see photo below).

They are a vital part of global communications and represent billions of dollars in investments, but once they break down or run out of fuel, they’re so much tin foil. DARPA has released a video outlining the agency’s vision of a mobile robotic servicing system designed to rendezvous with and repair ailing telecommunications satellites. Part of DARPA’s Robotic Servicing of Geosynchronous Satellites (RSGS) project, the concept video shows what such a system might look like and how it would operate. At its center is a robotic servicing vehicle (RSV), which sits in standby in geosynchronous orbit until it’s needed, such as when a satellite fails to deploy its solar panels or ends up in the wrong orbit. The RSV looks pretty much like a satellite with robotic arms and sockets for interchangeable manipulators, which are attached to it like a tool belt. When ordered, it can match orbits with the faulty satellite and fly around it as it collects images and 3D data, which it downloads to Earth for assessment. Based on the data, mission control develops a servicing plan using computer simulations that tell the RSV which tools to use and how to fix the problem. This service plan is then confirmed by laboratory rehearsals before being transmitted to the RSV.

Once programmed, the RSV tools up, then approaches and docks with the malfunctioning target satellite. After docking, a ground operator makes a detailed assessment of the satellite and compares the new data against the plan. When given the green light, the RSV carries out the repairs or uses its engine to move the satellite into its proper orbit.

DARPA says that it envisions the RSV in orbit within five years. If successful, the DARPA-developed toolkit module will be attached to a commercial space vehicle to create a commercially owned and operated RSV, which could lower the cost of operating geosynchronous satellites.