Photonic computers could run 20 times quicker than today’s laptops if microchips could process data in speedy photons. Now, they might be able to. For the very first time, researchers from two Australian universities have found a way to store light waves as sound waves in a microchip – a breakthrough that brings us closer to the super-fast computers of the future. For the first time ever, scientists have stored light-based information as sound waves on a computer chip – something the researchers compare to capturing lightning as thunder. While that might sound a little strange, this conversion is critical if we ever want to shift from our current, inefficient electronic computers, to light-based computers that move data at the speed of light. Light-based or photonic computers have the potential to run at least 20 times faster than your laptop, not to mention the fact that they won’t produce heat or suck up energy like existing devices. This is because they, in theory, would process data in the form of photons instead of electrons. We say in theory, because, despite companies such as IBM and Intel pursuing light-based computing, the transition is easier said than done. Coding information into photons is easy enough – we already do that when we send information via optical fibre. But finding a way for a computer chip to be able to retrieve and process information stored in photons is tough for the one thing that makes light so appealing: it’s too damn fast for existing microchips to read. This is why light-based information that flies across internet cables is currently converted into slow electrons. But a better alternative would be to slow down the light and convert it into sound. And that’s exactly what researchers from the University of Sydney in Australia have now done. “The information in our chip in acoustic form travels at a velocity five orders of magnitude slower than in the optical domain,” said project supervisor Birgit Stiller. “It is like the difference between thunder and lightning.”

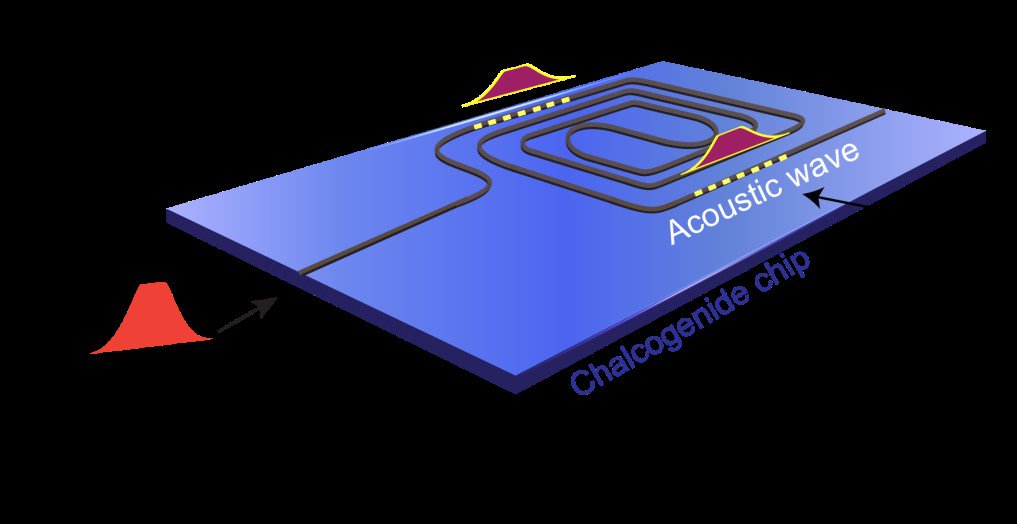

This means that computers could have the benefits of data delivered by light – high speeds, no heat caused by electronic resistance, and no interference from electromagnetic radiation – but would also be able to slow that data down enough so that computers chips could do something useful with it. “For [light-based computers] to become a commercial reality, photonic data on the chip needs to be slowed down so that they can be processed, routed, stored and accessed,” said one of the research team, Moritz Merklein. “This is an important step forward in the field of optical information processing as this concept fulfils all requirements for current and future generation optical communication systems,” added team member Benjamin Eggleton. The team did this by developing a memory system that accurately transfers between light and sound waves on a photonic microchip – the kind of chip that will be used in light-based computers. First, photonic information enters the chip as a pulse of light (yellow), where it interacts with a ‘write’ pulse (blue), producing an acoustic wave that stores the data. Another pulse of light, called the ‘read’ pulse (blue), then accesses this sound data and transmits as light once more (yellow). While unimpeded light will pass through the chip in 2 to 3 nanoseconds, once stored as a sound wave, information can remain on the chip for up to 10 nanoseconds, long enough for it to be retrieved and processed. The fact that the team were able to convert the light into sound waves not only slowed it down, but also made data retrieval more accurate. And, unlike previous attempts, the system worked across a broad bandwidth. “Building an acoustic buffer inside a chip improves our ability to control information by several orders of magnitude,” said Merklein. “Our system is not limited to a narrow bandwidth. So unlike previous systems this allows us to store and retrieve information at multiple wavelengths simultaneously, vastly increasing the efficiency of the device,” added Stiller. The research has been published in Nature Communications.