Released the First-Ever Image of a Black Hole

What Am I Looking At?

For the first time, we can directly observe a black hole as it sucks light and matter beyond the point of no return.

On Wednesday, an international coalition of scientists that came together to form the Event Horizon Telescope — more on that later — announced via livestream that they had captured direct images of a supermassive black hole in the M87 galaxy. These images signify that scientists have finally seen, first hand, celestial bodies that up until recently were only assumed to exist.

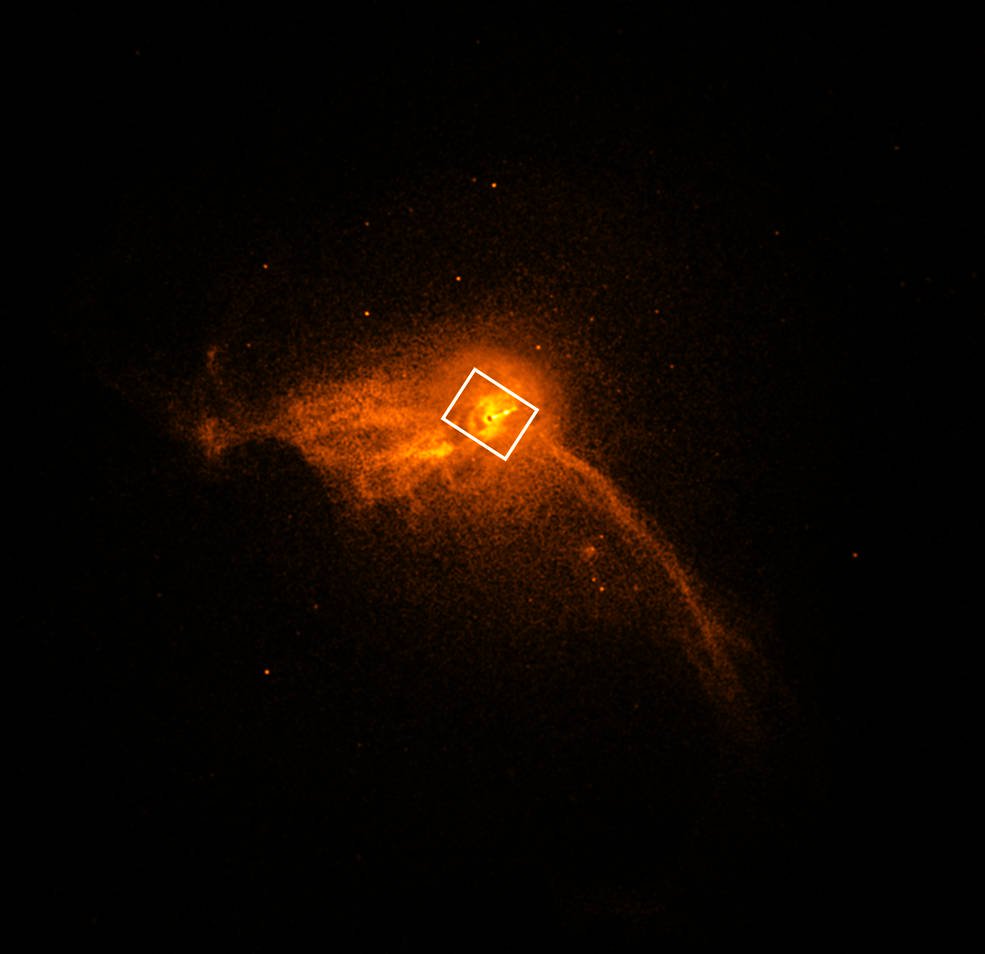

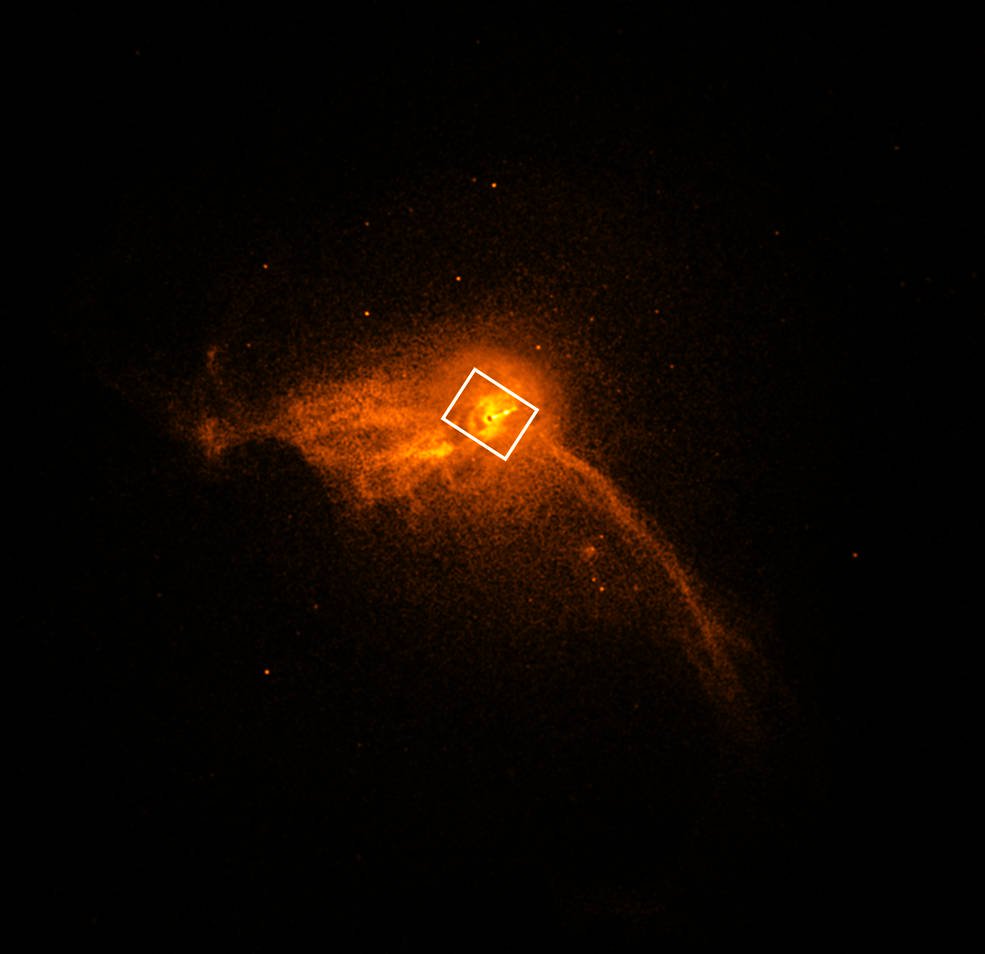

That right there is the supermassive black hole M87

Chandra X-ray Observatory close-up of the core of the M87 galaxy.

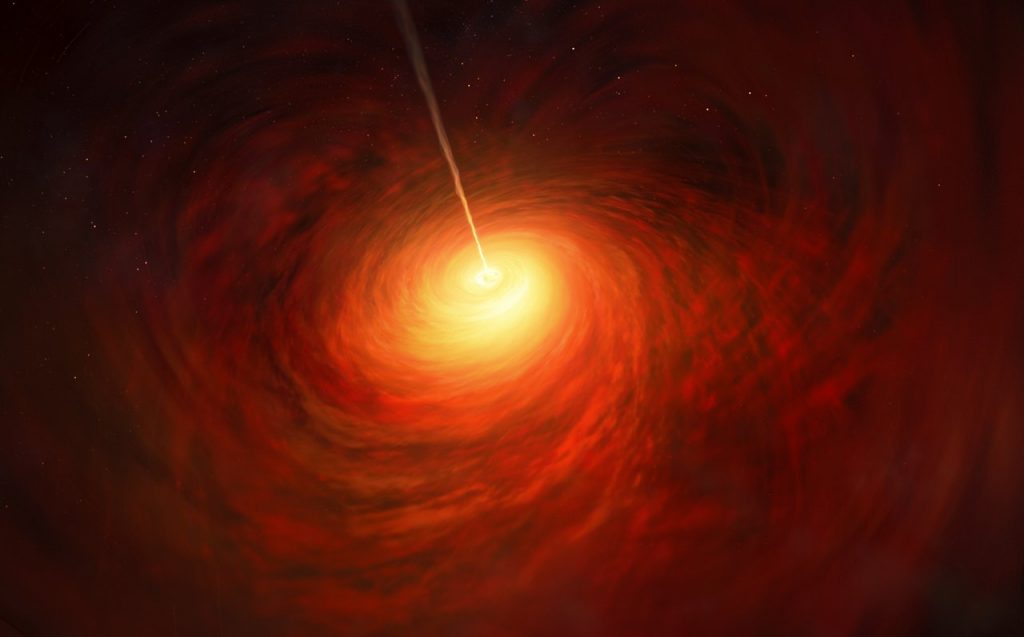

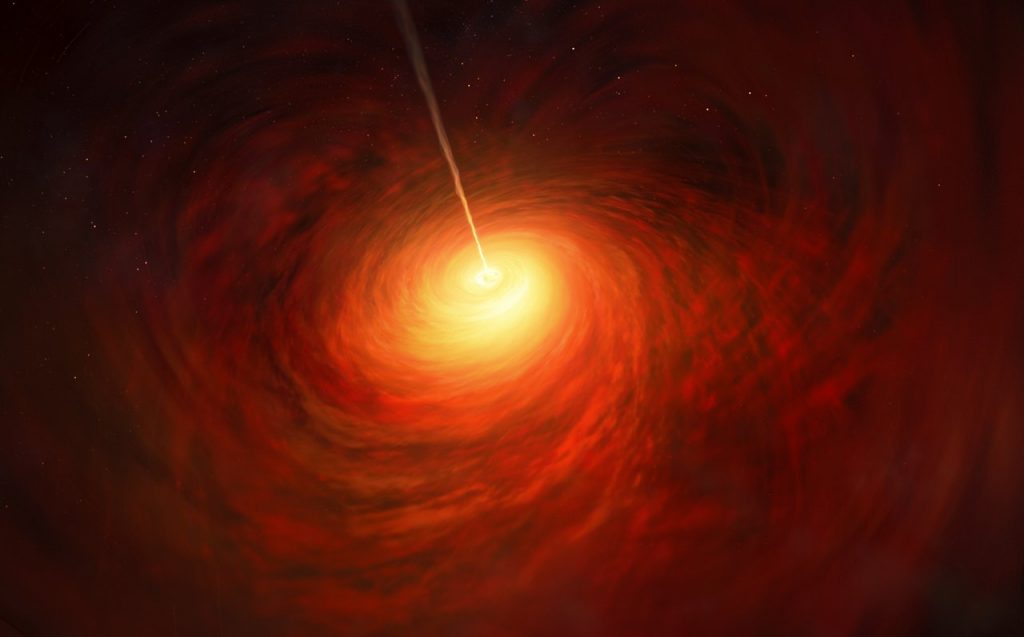

Artist’s impression of M87*, showing the relativistic jet, and superheated material around it.

What Took So Long?

For how immensely powerful they are, black holes are surprisingly tiny on a cosmic scale.

According to Vox, for instance, it’s comparable to standing on Earth and taking a picture of a DVD that someone left on the moon.

Spotting such a small object from so far away requires a gigantic telescope — so scientists built one as big as the Earth, appropriately named the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT).

“It’s the equivalent of being able to read the date of a quarter in Los Angeles while we’re standing here in Washington D.C.,” said EHT Director Shep Doeleman during a live stream. “We’ve exposed part of the universe that was invisible to us before.”

How Does It Work?

The EHT is a network of eight telescopes from around the world that are all taking in the same data.

The network relies on a technique called very-long-baseline interferometry, by which each telescope receives the same signal. Because those signals will inherently reach each telescope at a slightly different time, scientists can combine each individual scope’s data, treating the network as though it was one, giant, Earth-sized telescope.

The resulting files are massive — so much so that they had to be stored on physical hard drives and flown to a location where researchers combined them into one aggregate image. This limitation delayed the project, as the telescope in Antarctica was inaccessible for several months during the winter, according to Vox.

Once scientists had access to the data, they began the arduous task of merging each telescope’s results into the final research, accounting for minutia that risked throwing off the findings such as the Earth’s rotation.

It Looks Familiar

We’ve been looking at artists’ renditions and data visualizations of black holes for years. These renditions tend to show a black sphere surrounded by a big, sometimes fiery starscape. This actual image looks similar to those renderings — the silhouette of the black hole is illuminated by all of the stuff entering its event horizon. Technically, because the black hole’s pull is so strong, we’re observing the stuff behind it that’s been warped all the way around by an immense gravitational force.

As the YouTube account Vertasium explained, black holes are surrounded by a nearby layer of spiraling light warped by the black holes’ gravity, orbiting around the black holes in such a perfect sphere that if one were to walk into it, they would be able to see the back of their heads.

Because the light observed by the EHT has warped around the black hole before traveling to Earth, the shadow we see is actually the entire surface of the black hole, as though it had been ripped open and flattened like a pancake, surrounded by a disk of orbiting light.