We may be one step closer to cracking the Mars methane mystery.

NASA’s Curiosity rover mission recently determined that background levels of methane in Mars’ atmosphere cycle seasonally, peaking in the northern summer. The six-wheeled robot has also detected two surges to date of the gas inside the Red Planet’s 96-mile-wide (154 kilometers) Gale Crater — once in June 2013, and then again in late 2013 through early 2014.

These finds have intrigued astrobiologists, because methane is a possible biosignature. Though the gas can be produced by a variety of geological processes, the vast majority of methane in Earth’s air is pumped out by microbes and other living creatures.

Some answers may soon be on the horizon, because that June 2013 detection has just been firmed up. Europe’s Mars Express orbiter noted the spike as well from that spacecraft’s perch high above the Red Planet, a new study reports.

“While previous observations, including that of Curiosity, have been debated, this first independent confirmation of a methane spike increases confidence in the detections,” said study lead author Marco Giuranna, of the Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica in Rome.

And that’s not all. Giuranna and his team also traced the likely source of the June 2013 plume to a geologically complex region about 310 miles (500 kilometers) east of Gale Crater.

Whiffs of Gale Crater air

The researchers used data gathered by Mars Express’ Planetary Fourier Spectrometer instrument (PFS), which also sniffed out traces of Red Planet methane back in 2004. (The spacecraft has been orbiting Mars since December 2003.)

Giuranna, the PFS principal investigator, had prepared for synergy with the Curiosity team. Soon after the rover’s August 2012 touchdown inside Gale, he decided to monitor the air above the crater over the long term, Giuranna said.

It’s tricky to measure Red Planet methane from Mars orbit, for a variety of reasons, including the gas’s low abundance and weak absorption. (It’s no picnic measuring Mars methane from Earth, either, because the much more plentiful methane in our planet’s atmosphere can complicate observations and interpretations. These factors help explain the debate Giuranna referenced above.)

So, Giuranna and his colleagues developed a new approach to PFS data selection, processing and analysis. For the new study, they applied this approach to measurements made over Gale Crater during the first 20 months of Curiosity’s mission on Mars.

They found one hit: a peak of about 15.5 parts per billion (ppb) methane by volume on June 16, 2013. That was just one Martian day after Curiosity detected a peak of nearly 6 ppb.

“We were very lucky, as this is not the result of coordinated observations,” Giuranna told Space.com via email. “Just by chance!”

By the way, background methane levels in Gale Crater’s air, as measured by Curiosity, range from about 0.24 ppb to 0.65 ppb.

The study team also homed in on the methane plume’s possible source region, using two independent approaches.

The researchers divided the area around Gale Crater into a series of squares, each of which measured nearly 155 miles (250 km) on a side. They then used computer simulations to create 1 million methane-release scenarios for every square, to assess the probability of each one as a source for the Gale gas. The scientists also studied the geology of each square, looking for features that might be associated with methane emission, such as fault lines and fault intersections.

“Remarkably, we saw that the atmospheric simulation and geological assessment, performed independently of each other, suggested the same region of provenance of the methane, which is situated about 500 km east of Gale,” Giuranna said. “This is very exciting and largely unexpected.”

That potential source region may contain methane trapped beneath ice, he added.

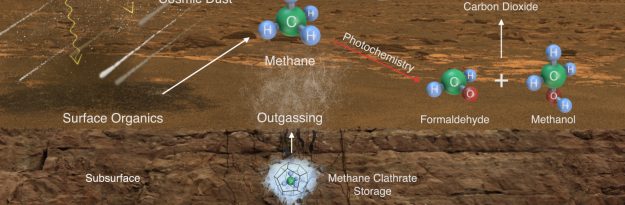

“That methane could be released episodically along faults that break through the permafrost due to partial melting of ice, gas pressure buildup induced by gas accumulation during migration, or stresses due to planetary adjustments or local meteorite impact,” the researchers wrote in the new study, which was published online today (April 1) in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Still lots of work to do

The paper doesn’t address the ultimate origin of the methane — whether it was churned out by Martian microbes or reactions involving hot water and certain types of rock. And scientists don’t know if the detected methane was produced recently or long ago; it could have been trapped under the ice for eons, after all.

But the new study could help researchers get to the bottom of such questions eventually. For example, Mars Express will eye the potential source region in detail in the future, Giuranna said. And other spacecraft, such as the methane-sniffing Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) — part of the European-Russian ExoMars program — may do so as well.

Indeed, Giuranna’s team is involved with the TGO mission, which arrived at Mars in October 2016. And coordinated TGO-Mars Express measurements are in the works. The PFS team also aims to apply its new analysis techniques to the instrument’s entire data set, Giuranna said.

“Follow-up is very important to better understand methane on Mars,” he said. “We are collecting pieces of a puzzle and need more pieces to understand better what is going on.”