Saturn just hasn’t been itself lately. About a decade ago, one of its periodic super storms erupted way ahead of schedule. Now astronomers report on a kind of cyclone in the planet’s far north that nobody has ever seen before.

Most storms on Saturn are either small puffs of cloud that vanish in days, or monstrous plumes that take months to dissipate. The newly observed phenomenon lies somewhere in between, and it could help us better understand what lurks beneath the giant planet’s cover.

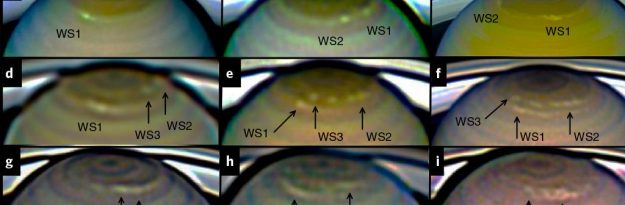

Telescope imagery taken of the ringed world last year revealed long patches of bright cloud blossoming near Saturn’s north pole on four separate occasions between March and October.

Researchers recently analysed hundreds of snapshots of the phenomenon taken by amateur astronomers, to develop simulations that might explain the strange weather events.

Stretching a distance of between 4,000 and 8,000 kilometres (almost 2,500 to 5,000 miles), the white patches are more than double the size of the usual cyclonic activity that pops up from time to time in Saturn’s golden bands.

They also took their sweet time to fade away again, overlapping one another as new cyclones emerged. One endured for a whole 214 days.

As big as they were, none came close to matching the seasonal spectacles known as Great White Spots. Seen on just seven occasions since 1876, these huge storms seem to erupt every 28.5 years, coinciding with the planet’s northern summer.

The almost-clockwork beasts can be 10 times larger than their smaller cousins, wrapping their tails right around the globe and taking months to simmer down.

In 2010, a Great White Spot close to the equator not only stole the show in terms of scale and power, outdoing previous storms, but was remarkably premature, appearing a full decade ahead of expectations.

Fortunately we had Cassini in the neighbourhood to provide an unprecedented view of the storm, helping researchers better understand the cause of these dynamic affairs.

Today, scientists suspect the huge storms are caused by cycles of cooling that contract lighter gases in the upper atmosphere, sending them below wet, heavy layers of cloud deeper down, and forcing them to lift and shed their warmth.

Made mostly of hydrogen and helium, Saturn’s overall density is less than water, meaning it would bob around in a bathtub big enough to hold it. But there are other gases in the mix as well, including trace amounts of water and ammonia, and hydrocarbons like methane and propane.

Layers of these gases whip about in currents that can reach speeds of 1,800 kilometres per hour (over 1,100 miles per hour) near the equator; more than four times as fast as our own planet’s fastest winds.

A great deal of the gas giant’s activity is driven by energetic processes of rising and falling fluids and the planet’s speedy rotation. So, the question is how these new observed events fit into Saturn’s big weather picture.

Although they weren’t as impressive as the Great White Spots, the appearance of the four cyclones comes at just the right time to make some astronomers wonder if they’re simply undernourished cyclone events, after the 2010 storm somehow sapped their strength.

They also appeared at latitudes suspiciously similar to one that previously hosted a Great White Spot in the 1960s, and fall into line with a 60-year cycle of Great White Spots in the same part of the world.

Simulations run by the research team estimated that the kind of energy needed to spark these four medium-sized events would be 10 times more than that needed for smaller storms, but 100 times less than what would be needed for a Great White Spot to occur.

It’s not enough to definitively show exactly what’s behind these storms, but their long-lasting nature strongly suggests something is feeding their fury deep beneath the clouds.

Not everybody is convinced that these mediocre white puffs are super storms that failed to warm up, though, given the two events occurred so far apart. They could be unique events in their own right.

Time will tell. With so many eyes on the planet – both amateur and professional – we’re sure to learn more about Saturn’s strange behaviour in coming years.

This research is published in Nature Astronomy.