In july 2014 Britain and France embarked on a path to develop an unmanned combat air vehicle (UCAV). There is now growing consensus on the planform of the aircraft, and while decisions about an engine selection remain sensitive, industry officials are hopeful that some significant milestones can be made public toward the middle of this year.

But challenges remain, indeed the political cycles of the U.K. and France do not align, with key elections offset by two years, yet support for the project appears strong.

The FCAS (Future Combat Air System) feasibility study is led by the defense procurement agencies of Britain and France and driven by six industry partners: airframers BAE Systems and Dassault Aviation, defense electronics companies Thales and the Selex unit of Finmeccanica, and by aero-engine companies Rolls-Royce and Snecma. Every day French engineers are working hand in hand with their British colleagues at Warton as well as at other sites in France and Britain.

With the two-year project running until this October, the teams are now entering a more administrative phase that will consolidate their findings in the hope that the studies could push into the next phase, perhaps a development program beginning in 2017.

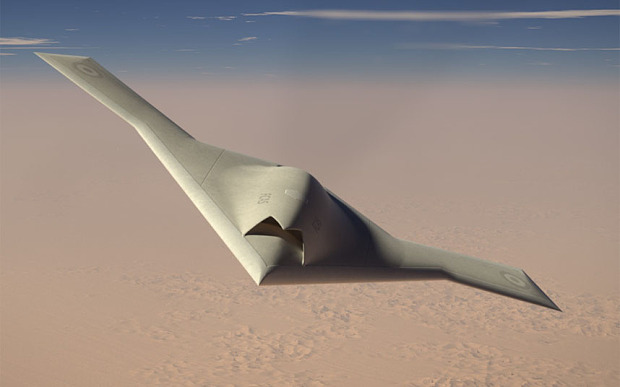

In mid-2015, French officials said the study was looking at three options for the planform: a single swept leading-edge like that on Neuron and Taranis; a double leading-edge as on the Northrop Grumman X-47, or an X-45 style configuration with a fuselage and swept wings. While the decision is not being made public, the aircraft’s size is becoming more tangible.

The fuel fraction needed to provide a loiter capability and payload provision for internal weaponry and sensors may likely drive the final design toward the length of a Eurofighter Typhoon, but with perhaps twice the wingspan.

An airframe so large could require a second engine. Among the biggest challenges of FCAS development, however, will be defining the architecture to operate the system.

There are currently two schools of thought as to how a future UCAV could be used. The most obvious way is as an independent platform with one or two systems working independently or together to gain access into hostile airspace, either to find targets and mark their position for standoff weapons, or to engage them itself using onboard weapons.

Such capabilities have already been tested on the Taranis, where the aircraft was asked to locate a target autonomously using its sensor and then engage it albeit, with Taranis, in a simulated fashion.

The other way the UCAV could be used is as an adjunct to a manned platform such as the Typhoon or F-35, “adding capabilities to manned platforms in the same way we might integrate a weapon or a sensor onto a manned platform,” Nigel Whitehead, BAE Systems group managing director of programs and support, told an audience at the Royal Aeronautical Society in December.

Such a platform, he said, could act as a ride-along bomb bay capable of carrying additional weaponry to support a manned strike. Alternatively, it could be commanded to advance into contested airspace to improve target identification, keeping manned aircraft out of harm’s way.

“You can use a UCAV in a number of different ways—operate them independently or make your Typhoon force more effective . . . and [so] we are having this debate,” says Rowe-Willcocks. UCAVs also will not be “dogfighting,” he notes; there will still be a need for manned fighters for air-to-air combat for some time to come.

The FCAS team has taken lessons from both the British Taranis program and the joint European Neuron, led by France. Rowe-Willcocks says that even though both platforms are powered by the same Rolls-Royce Adour engine, the integration of the engine into the platform is “very different.” In addition, while the French chose to incorporate weapon delivery into Neuron, BAE Systems chose to insert what it calls a “high level of automation and survivability technologies.”

Rowe-Willcocks says BAE will be able to draw on a basket of different technologies. The British Astraea (Autonomous Systems Technology Related Airborne Evaluation & Assessment), which ended in late 2015, had studied the aerial refueling of autonomous platforms in conjunction with Cobham in 2011, while weapon-firing was performed as part of development work when BAE’s Herti system launched a Thales Lightweight Multirole Missile.

Part of the FCAS team’s work is looking at how the aircraft can be built more cost-effectively and developed more quickly than its manned predecessors. Notably, the teams are looking at processes and software toolsets developed for the automotive industry to speed that work.