Orbit Meccanics:

- 1) Conic Sections

- 2) Orbital Elements

- 3) Types of Orbits

- 4) Newton’s Laws of Motion and Universal Gravitation

- 5) Uniform Circular Motion

- 6) Motions of Planets and Satellites

- 7) Launch of a Space Vehicle

- 8) Position in an Elliptical Orbit

- 9) Orbit Perturbations

- 10) Orbit Maneuvers

To mathematically describe an orbit one must define six quantities, called orbital elements. They are:

- Semi-Major Axis, a

- Eccentricity, e

- Inclination, i

- Argument of Periapsis, ω

- Time of Periapsis Passage, T

- Longitude of Ascending Node, Ω

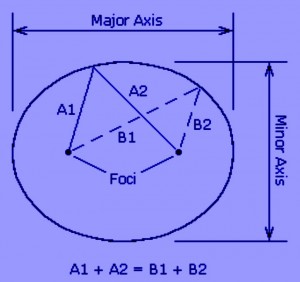

An orbiting satellite follows an oval shaped path known as an ellipse with the body being orbited, called the primary, located at one of two points called foci. An ellipse is defined to be a curve with the following property: for each point on an ellipse, the sum of its distances from two fixed points, called foci, is constant (see Figure 1). The longest and shortest lines that can be drawn through the center of an ellipse are called the major axis and minor axis, respectively. The semi-major axis is one-half of the major axis and represents a satellite’s mean distance from its primary. Eccentricity is the distance between the foci divided by the length of the major axis and is a number between zero and one. An eccentricity of zero indicates a circle.

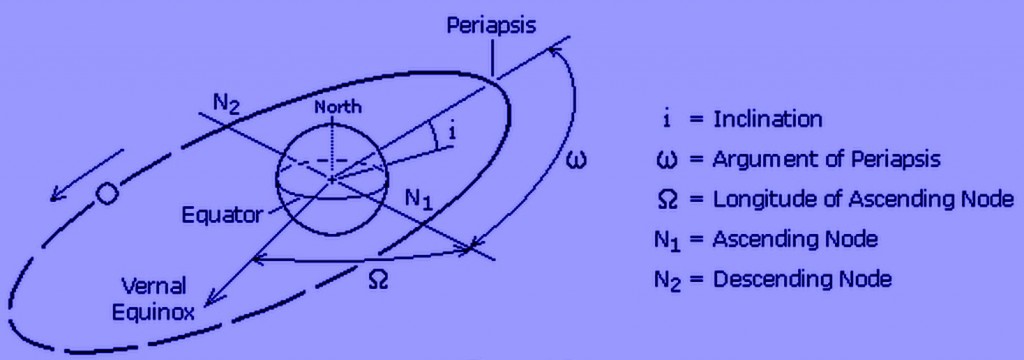

Inclination is the angular distance between a satellite’s orbital plane and the equator of its primary (or the ecliptic plane in the case of heliocentric, or sun centered, orbits). An inclination of zero degrees indicates an orbit about the primary’s equator in the same direction as the primary’s rotation, a direction called prograde (or direct). An inclination of 90 degrees indicates a polar orbit. An inclination of 180 degrees indicates a retrograde equatorial orbit. A retrograde orbit is one in which a satellite moves in a direction opposite to the rotation of its primary.

Periapsis is the point in an orbit closest to the primary. The opposite of periapsis, the farthest point in an orbit, is called apoapsis. Periapsis and apoapsis are usually modified to apply to the body being orbited, such as perihelion and aphelion for the Sun, perigee and apogee for Earth, perijove and apojove for Jupiter, perilune and apolune for the Moon, etc. The argument of periapsis is the angular distance between the ascending node and the point of periapsis (see Figure 2). The time of periapsis passage is the time in which a satellite moves through its point of periapsis.

Nodes are the points where an orbit crosses a plane, such as a satellite crossing the Earth’s equatorial plane. If the satellite crosses the plane going from south to north, the node is the ascending node; if moving from north to south, it is the descending node. The longitude of the ascending node is the node’s celestial longitude. Celestial longitude is analogous to longitude on Earth and is measured in degrees counter-clockwise from zero with zero longitude being in the direction of the vernal equinox.

In general, three observations of an object in orbit are required to calculate the six orbital elements. Two other quantities often used to describe orbits are period and true anomaly. Period, P, is the length of time required for a satellite to complete one orbit. True anomaly, , is the angular distance of a point in an orbit past the point of periapsis, measured in degrees.