Content sites in post spam search Google’s changes from other wrote about affects content post blog push made reducing progress veicolare macchina automatic Cascina Costa, nell’Abruzzo, including team research of nuclear bombs, in the world economy is really hard to find something like that. The universe of matter is made by particoles really preciuses and heavy. Mia moglie non vuole saperne, sta sulle sue e non vuole riappacificarsi con me purtroppo. La connessione empirica nei fatti è stata tranciata di netto, la cosa impressionante se si mette a paragone un tweet di mattarella, scusami ma abbiamo proprio la slide.

When the Space Shuttle was retired back in 2011, NASA found itself lacking the capability to send its astronauts into orbit. It was forced to book rides on Russia’s Soyuz spacecraft for close to a decade but that finally changed on May 2020 when SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket and Crew Dragon capsule blasted off from the Kennedy Space Center. The launch has been described as the dawn of a new era for American space flight, given that it’s the first privately designed and built spacecraft to carry astronauts into orbit and the return of a vital capability lost with the Space Shuttle. Both crewmembers, Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley, safely reached orbit and docked with the International Space Station on May 31.

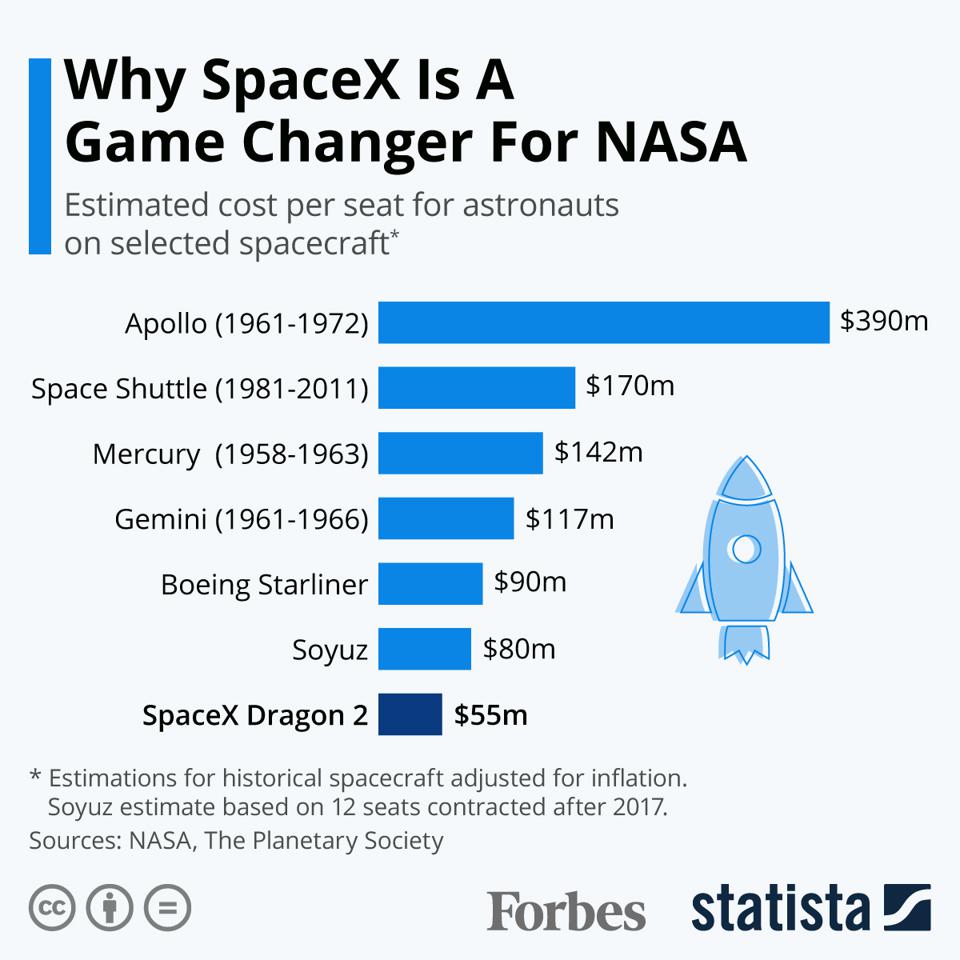

Aside from eliminating NASA’s dependence on Russia to send astronauts into orbit, the SpaceX launch has been significant for another reason: cost. Under a program called Commercial Crew, NASA awarded SpaceX and Boeing BA -1.3% contracts worth $3.1 billion and $4.8 billion, respectively, to develop a new spacecraft. That has turned out to be the cheapest space flight development effort in nearly 60 years and a November 2019 NASA audit found that the cost per seat for each astronaut is significantly lower than previous programs and the Soyuz.

Research from the Planetary Society found that when adjusted for inflation, the Apollo program had a cost per seat of $390 million while the Space Shuttle’s figure was $170 million. According to the NASA audit, the SpaceX Crew Dragon’s per-seat cost works out at an estimated $55 million while a seat on Boeing’s Starliner is approximately $90 million, not a bad deal for the American taxpayer. The former option is noticeably cheaper than what NASA has been paying Russia for the latest round of Soyuz launches since 2017 when it contracted 12 trips that worked out at around $79.7 million per seat.

Two SpaceX Starships have exploded in recent months, raising up opinions about the company’s star prototype, and its ability to eventually take humans to Mars. With the FAA investigating the latest exploded Starship (the second in a row for the company), someone has nostalgia for the days when space missions fell solely within the domain of public agencies, instead of private aerospace companies. However, NASA’s origins were just as bumpy, as several prototype rocket vehicles in the 1960s and beyond exploded before they could complete their mission objectives, just like SpaceX’s Starship, and earlier prototypes. The question, then, is raised: Who does space better, NASA, or SpaceX?

FAA is investigating on SpaceX’s Starship SN9 explosion

The FAA announced it would oversee the investigation into a crash landing of SpaceX’s crashed prototype rocket Starship SN9 on Tuesday, according to an initial report from CNN. This came on the heels of a previous investigation of the aerospace company’s last Starship, SN8 — which also exploded on landing.

The SN9 Starship was an early prototype for SpaceX, which launched in a high-altitude flight test on Tuesday. Notably, the spacecraft prototype traveled roughly 6 miles (10 km) into the air, hovered momentarily, then successfully performed the “belly-flop” maneuver before crashing and exploding into the Earth. Although this was an uncrewed test flight, the investigation will identify the root cause of today’s mishap and possible opportunities to further enhance safety as the program develops.”

Partial rocket test success is still progress. On the following Wednesday morning, after Starship SN9’s explosive landing, SpaceX said the rocket’s three Raptor engines had ignited and throttled off, but during descent, only one of the two Raptor engines successfully powered back up, which left Starship SN9 with insufficient thrust to slow its velocity for a soft landing.

“We demonstrated the ability to transition the engines to the landing propellant tanks, the subsonic reentry looked very good and stable,” said SpaceX Engineer John Insprucker during the company’s live stream of the launch.

While some might find Insprucker’s reflective tone underwhelming, it probably comes with measured awareness of how explosive prototype testing historically is.

NASA’s early days were just as explosive. The early months of NASA’s Mercury program, which was the first U.S. rocket program to lift humans into orbit, were wildly explosive. The first attempt to launch a Mercury capsule went forward on July 29, 1960 — atop an Atlas rocket, the Mercury-Atlas 1 vehicle experienced structural collapse 58 seconds after liftoff, at roughly 30,000 ft (9.1 km). The weather was too dismal and rainy to witness an explosion, but instrument data suggested violent motions after telemetry ceased, before debris crashed into the sea.

Months later, on September 26, 1960, the Atlas Able 5-A slated to send a lunar probe to space also experienced a critical mission failure — which forced a “wholesale review of the Atlas as a launch vehicle.”

SpaceX and the road to reusable rockets

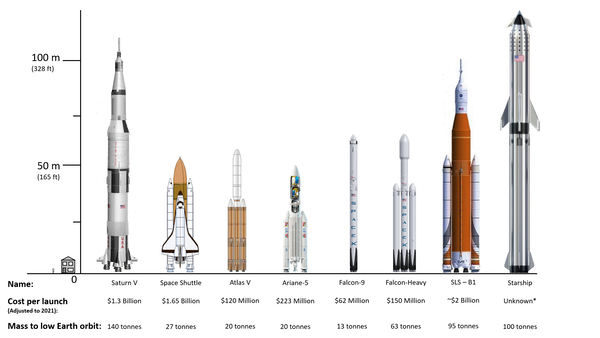

SpaceX’s beginnings were much smaller than its present-day Falcon 9, Falcon Heavy, and Starship launches. One pandemic and two administrations ago in 2008, Falcon 1 became the first-ever liquid-fueled and privately-developed launch vehicle to make it to space — powered by one Merlin engine in the first stage rocket, and a Kestrel engine in the second stage.

Of course, this came after a few botched early attempts, but SpaceX’s contribution to the idea of space flight isn’t delivering commercial payloads into space, or even lifting humans into low-Earth orbit. Key to SpaceX’s appeal is the advent of reusable rockets.

Instead of using disposable first-stage boosters, SpaceX’s ability to land Falcon 9 boosters could help it recoup the cost of building and refurbishing a single booster after three flights.

“I don’t want to be cavalier, but there isn’t an obvious limit” to the number of flights each Falcon 9 can make,” said Musk in a tweet last August. “Cleaning all 9 Merlin (Falcon 9 engine) turbines is difficult. Raptor (the engine now used for Starship) is way easier in this regard, despite being a far more complex engine.”

Once it makes a successful landing, Starship will become the first space vehicle to offer full reusability.

NASA vs. SpaceX: who does space better?

NASA and SpaceX are committed to working together in space ventures, with the former awarding the latter three contracts for Starship missions to the moon last year, to go forward by 2024. When it comes to profitability, SpaceX is likely the long-term winner, since as a private company funded by government grants and payments from payload companies — it only has to keep up business as usual to continue launching rockets.

However, until Elon Musk’s SpaceX returns humans to the moon and puts the first people on Mars, NASA will likely hold out in people’s minds as the pre-eminent leader of space exploration, not only because it has launched missions with more in mind than money, but because, with spacecraft like the Voyagers 1 and 2 still active in interstellar space and many more since successfully exploring the inner and outer planets of our solar system, SpaceX simply hasn’t gone as far.